Archaeological Prospections in the Argly Valley System (Northern Tadjikistan) in 2006

Overview

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Results in 2006

1. Introduction

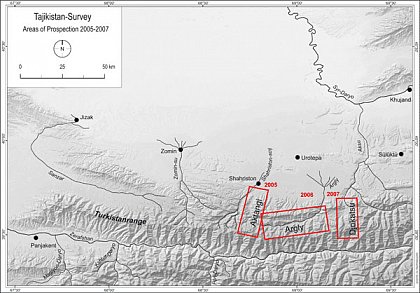

The field season 2006 was focused on the Argly valley system which is located in the central section of the prospection area (fig. 1). Fieldwork took place from July 10th to August 25th. The joint Tadjik-German team consisted of U. Eshankulov, N. Rahimov, M. Gütte, A. Puk, and S. Stark.

Figure 1: Areas of prospections 2005-2007

With an east-west-extension of ca. 50 km the Argly system is the most most extensive of the valley systems under prospection (fig. 2). It is made up by two branches of a main valley (Argly branch and Uguk-sai branch) and 18 major tributary valleys. The two main branches join about 4-5 km to the north-east of the kishlak Ovchi. After the confluence of both sais the river is generally called Basmanda-sai.

Figure 2: The Argly system with major tributaries

In contrast to the neighbouring Aktangi system the Argly valley is comparatively dry (fig. 3). Nevertheless, the upper parts of the valley system, above ca. 2800 m, still offer excellent pasture grounds in the period from June to September.

Figure 3: View from the ridge of the Turkestan range into the Novoli valley/upper section of the Argly system

Today the upper part of the valley system is completely deployed of permant settlements, only a handfull of seasonal hamlets and single farmsteads can be observed. Apart from marginal rainfall farming (lalmī) in the bottom of the valleys up to 2900 m (with crops such as barley, oat and rye) transhumant stockbreeding is clearly prevailing in the upper sections of the valley system (fig. 4).

Figure 4: Summer pastures in the upper Hoki Safed valley

Below approximately the 2600 m elevation line the valley becomes substantially broader and changes its appearance: Intensive irrigation farming is prevailing, which sustaines the two medium sized kishlaks of Ovchi and Uguk (fig. 5).

Figure 5: Lower Argly valley around Ovchi

Only the area of Ovchi and Uguk, that is the lower sections of the Argly system, have been subject to archaeological and ethnographical investigations in the past. Publications mention an early-mediaeval fortress near Ovchi (Qal'a-i-Mugh),[2] a small tepa in the south-western margins of Ovchi,[3] a mediaeval stone column from the mazar of Hodja Abdullo Ansori in Uguk[4] and traces of irrigation work (aryks and karezes).[5] In contrast to that, the upper parts of the valley system have never before been subject to systematic investigations.

2. Results in 2006

Our field work was focused on surface prospections. Only exceptionally small test excavations were carried out. According to the ecological dichotomy of the valley system in an upper part (main valley and tributaries of the above the 2500 m elevation line; tributaries of the Uguk branch) and a lower part (main valley below the 2500 elevation line and main valley of the Uguk branch) the archaeological records from the two parts of the valley system differ substantially from each other and, therefore, will be presented separately.

2.1 The upper part of the Argly system

Archaeological records from the upper part of the Argly system constitute the following groups of material:

- A. Barrows

- B. Petroglyphs

- C. Remains of small hamlets respectively single farmsteads with traces of irrigation channels and field terraces

- D. Caves and Shelters

- E. Isolated stray finds

A. Barrows

In most of the tributary valleys above the 2500 m elevation line we were able to register at least 117 tumuli built from rubble (fig. 6). In all likelyhood they represent barrows (see also the results of test excavations below). It has to be noted that this number includes only larger barrows with diameters ranging from 3 to 28 m. The total number of burial mounts is substantially higher as smaller tumuli were difficult to trace individually and were, therefore, recorded only as "cemeteries". These new data clearly invalidate the older assertion that there are no substantial barrow grounds in Ustrushana.

Figure 6: Distribution of barrows in the upper Argly Valley system

Barrow sites are mainly located in the southern tributaries. A distinct maximum was recorded in the Duktchi valley (site Duktchi-1) with about 44 clearly discernable barrows of diameters ranging from 3 to 28 m (the artifical character of another 20 mounts can not be definitely established). Considerable accumulations of medium sized barrows were also registered in the two neighbouring tributaries with at least 12 barrows in the Novoli valley (sites Novoli-3-5) and 18 barrows in the Tuktchi valley (sites Tuktchi-1-3). In addition, groups of 2 or 3 barrows are distributed over larger areas in other tributary valleys (see distribution map in Figure 6). In addition to surface prospections 4 barrows of small and medium size at 3 different spots (Tuktchi-3a, Novoli-3 and Novoli-4) were excavated. Our test excavations have yielded the following results:

a) Barrow Tukchi-3a/1 (fig. 7)

Below a flat rubble tumulus (diameter ca. 6,50 m) a construction of an outer and an inner ovale of stone boulders and rubble can be traced. Both ovals are oriented in NW-SE axis; the outer oval measures NW-SE 3,60 m and 2,70 m SW-NE), the inner oval 2,80 m resp. 1,60 m (all measures respresent inside dimensions). The space between both ovals is filled with rubble. The inner oval represents the grave chamber in form of a flat pit (ca. 20 cm below ground level).

Figure 7: Barrow Tukchi-3a/1

The barrow yielded a single enterrement of unspecified gender which was situated in dorsal position oriented in SE-NW axis, with head pointing north-westwards. The only grave good which could be traced was a 17 cm long fragment of a slightly bent blade from an iron knife situated above the right humerus of the corpse.

Figure 8: Fragment of an iron knife from barrow Tukchi-3a/1

b) Barrow Tuktchi-3a/2 (fig. 9)

The tumulus is made of a flat rubble mound (diameter 7-8,75 m). The grave chamber is situated almost in the middle of the tumulus and forms a rectagular stone cist, made of stone boulders or upright stone slaps. It is oriented in NE-SW axis (inside dimensions ca. 2,45 x 1,02 m). It was covered by flat stone slaps and is set about 50 cm below ground level.

Figure 9: Barrow Tuktchi-3a/2

As the grave chamber contained neither any traces of an enterrement nor of grave goods we have reason to suppose the barrow to be a cenotaph burial. Few and highly fragmented sherds of hand-made pottery have been traced in the filling of the mound together with animal bones (sheep) and fire place traces.

c) Barrow Novoli-4

The superstructure of the tumulus resembles those of Tuktchi-3a (diameter ca. 7 m).

Figure 10: Tumulus of the Barrow Novoli-4 (after cleaning)

The grave chamber in form of a roughly rectangular stone cist, made of stone boulders or upright stone slaps, is oriented roughly in E-W axis. The chamber was originally covered by flat stone slaps which were partially collapsed into the cist. Due to very humid ground conditions the burial was badly preserved and difficult to trace. Still, traces of the cranium and a lower leg suggest a dorsal position oriented in E-W axis, with head pointing westwards. Apart from that, very few traces of an oblong iron object were traced on the left side of the enterrement, near to where the hip must originally have been situated.

d) Barrow Novoli-3

The flat rubble tumulus measures about 22,50 m in diameter. The burial was evidently plundered in Antiquity. The damage caused by the grave robbers made it impossible to trace the actual form of the grave chamber with certainty. Only the eastern part of the burial was left relatively untouched. There, bones from the lower legs upwards of one individual were preserved in anatomical order. Apart from that, parts of the cranium and of a lower leg of at least one more individual were recorded in the disturbed part of the grave chamber. The undisturbed parts of the corps might suggest supine position oriented roughly in E-W axis with head pointing westwards, thus similar to the three other burials from the upper Argly valley system excavated so far. Apart from human remains the filling of the grave chamber contained two very fragmented pottery sherds (base fragments), one of them re-used as a spindle whorl, the other one containing a potter's mark. Both fragments are hand made but it is difficult to chronologically specify them any further (a 5-6th century date might carryfully be suggested for at least the base fragment with the potter's mark). Furthermore it remains unclear if these fragments are part of the original burials or entered the filling later, during or after the robbery.

On the base of these data alone it is highly problematic to propose an exact dating for the barrows from the upper parts of the Argly system. There are certain features in grave construction and burial rite which have parallels in a rather broad chronological horizont - from late Bronze Age burials in western Ferghana (Kairakkum variant of Steppe bronze), certain burial types from cemetries of the Eilatan-Aktam-culture from south-eastern Ferghana to certain types of Kurum-burials mainly dating from the first century BC to the 6th/7th century CE. Regarding grave construction, these parallels pertain to flat grave pits of rectangular or oval layout, lined by small boulders or stones slaps, sometimes forming actual stone cists and frequently covered by flat stone slaps, sometimes overlapping each other, thus suggesting a kind of vault. Regarding burial rites parallels pertain to dorsal position, armes streched along the body, head pointing westwards, traces of ash and pottery sherds in the filling of the mounds and the coexistence of individual and collective burials. Unfortunately, the finding of only one fragment of an iron knife from barrow Tukchi 3a/1 and of some very fragmented sherds from Tukchi 3a/2 (which at least seem to be part of the original burial) do not allow a further specification in date than "early Iron Age to late Antiquity/early Middle Ages".

B. Petroglyphs

The discovery of petroglyphs in the course of our fieldwork in 2006 revealed a complex of archaeological material formerly unknown in Ustrushana. Interestingly, they only appear in the upper valley of the Novoli-sai which is one of the uppermost southern tributaries of the Argly (labelled as site "Novoli-2"). Here, we recorded a total of 63 stone boulders of different dimension with rock drawings.

Figure 11: Archaelogical sites from the Novoli valley

Figure 12: Stone boulder with petroglyphs from the Novoli valley

In terms of technique these rock drawings are fairly homogeneous - most of them are punched in darkish stone patina; only rarely drawings are craved into the patina with some spiky instrument. The dominating motif of the rock drawings from Novoli is the ibex (capra aegagrus), either as a single figure or as part of larger, multi-figured scenes (fig. 12).

Figure 13: Sample of rock drawings from Novoli-2

Within this group a whole range of stylistic variants is evident. The only other animal species which can be identified with certainty in the rock drawings from Novoli is the Bactrian camel (camelus bactrianus; cf. Fig. 12/VIIIc). However, some animal depictions might represent dogs, in two cases horns are styled like antlers - so these representations might be interpreted as deers or the like (fig. 12/XVIIIc and XXVIc). In addition, in one case (fig. 12/XXXIXa) an ibex is depicted with a very uncharacteristic long tail (similar to the one of a cat). Consequently, one might speculate if this drawing might represent rather a fantastic creature than an ordinary ibex. Depictions of human or human-like characters occur only very rarely in the petroglyphs from Novoli.

Figure 14: Sample of depictions of human figures from Novoli-2

A human figure can be found in a hunting scene (fig. 13/XXXIIb). But much more interesting is the representation of a human-shaped figure in a scene of unknown meaning (fig. 13/L): A human or human-like being, facing right is shown with raised arms, thus resembling the posture of an adorant; behind this figure (and partially merged with him) we find the depiction of an object in the form of an upright-standing oval. It is drawn in very broad contours and seems to be open towards its upper side. Behind this object there is the (incomplete) depiction of an upright standing ibex. Another upright standing ibex is given right above the human figure. Finally, two more upright standing ibexes are depicted to the left with their legs facing respectively merging into each other thus resulting in a heraldic motif. Interestingly, the exact findspot of the boulder containing this scene is located just a few meters beside the source of the Novoli-sai - a fact which might well have some relation to the meaning of this enigmatic scene. Finally, a group of motifs range from unanimated objects, such as the depiction of a chariot (fig. 14/XIXa), to various kinds of signs and symbols, some of them possibly tamghas (fig. 14).

Figure 15: Sample of depictions of unanimated objects from Novoli-2

Regarding the date of the new rock art complex from Novoli we are faced with the usual problems of dating petroglyphs. However, at least the above mentioned depiction of an chariot (fig. 14/XIXa) can be securely dated to the late Bronze Age, when this motif was widely distributed in the rock art of Central Asia. At the same time stylistic features of other drawings - such as angled legs - are reminiscent of the early Iron Age animal style (fig. 12/IIIa, IV, XXd, XLVIII). It is of little surprise that the new rock art complex from Highland Ustrushana offers - both in style and motif - plenty of parallels to the neighbouring rock art complexes in Matcha (upper Zarafshan), the Mogultau and in the Kurama range (western Ferghana/Ilak). As mentioned above, petroglyphs seem to be located only in the upper section of the Novoli-say valley (fig. 11). Possibly, this comparably remote high mountain valley was at some time considered as a "sanctuary in the open". This idea is further strengthened by traces of a "wall" constructed of upright set stone slaps and rubble which runs over the entire width of the lower Novoli valley (cf. map in fig. 11). Although it is impossible to give an exact date for this wall it has to be emphasized that the whole complex of petroglyphs is situated beyond this "wall" towards the mountains. Therefore, it might be suggested that this line (symbolically?) refers to a "sacred precinct" in the higher parts of the valley.

C. Remains of single farmsteds, field terrasses, enclosures and water installations

In roughly the same altitude sections as the barrows a whole series of single farmsteads, nearby field terraces, enclosures and remains of irrigation channels and the like was traced by surface prospections (figs. 16 and 17).

Figure 16: Single farmsteads, enclosures and water installations

Figure 17: Traces of a single farmstead at the site Baibiche-Kotin-9a

Their overwhelming majority is situated in the southern tributaries of the upper Argly. A clear maximum was recorded in the Kenkul valley and especially in the Baibiche-Kotin valley where they are distributed in a loose order over large parts of the valley. Only two "farmstead" structures were traced in the middle section of the Uguk-sai branch of the valley system (sites Uguk-2 and 3). In most cases traces of field terraces and aryks exist in the close neighbourhood of these sites. In terms of architecture these "farmsteads" resemble each other in layout: Remaining walls are set in rubble respectively small or medium sized stone boulders. Judging from contemporary analogies they represent the foundations of superstructures built from mud bricks and wood. The general outline of these buildings is roughly rectangular or angled (apart from protruding walls of entries and the like), the number of rooms of each structure ranges from two up to a dozen. Often one or two courtyards are attached. There are no traces of substantial cultural layers. The quantity of ceramic material from the surface is very insignificant. Generally this material can be dated from the 7/8th to the beginning of the 13th century. The repertoire of types and forms of vessels as well as their decoration have evident analogies in the material of the neighbouring Aktangi valley system - with two noteworthy exceptions: 1. In contrast to the record of the Aktangi valley (cf. sites Aktangi-2 and Hodja-Mazori-Tug) there are only very few examples of glazed pottery from sites in the upper Argly system. 2. Traces of ancient metallurgy such as slags and furnace fragments are completely lacking from the "farmstead" sites. Thus, despite of resemblances with settlement sites from the neighbouring Aktangi valley there exist some notable differences: Apart from the almost complete lack of glazed pottery and the complete absence of traces of metallurgy, differences pertain to architecture (single farmsteads instead of small settlements) and the location of these mediaeval farmsteads at a surprisingly high elevation up to 2900 m (whereas the Aktangi sites were confined to altitudes up to 2400 m). This points to a character of these sites which is generally different from the one of the Aktangi settlements: In contrast to the Aktangi settlements the farmsteads in the upper Argly system seem to have been essentially seasonal in character. Until today similar seasonal farmsteads can be observed in the same altitude section of the valley system. Yet another aspect is suggested be contemporary analogies: Today, a good part of the inhabitants of seasonal farms in the Upper Argly system originates from the upper Zarafshan valley, that is from beyond the mountain range. There, agricultural resources are scarce, which nowadays forces people from Aini and Matcha to use the upper Argly valley from spring to early autumn for tending their herds (sheep, goats, cows) and cultivating barley, ray and oat. A similar seasonal pattern of land use might be suggested for the pre Mongol farmsteads in question: The general prosperity of Mawarannahr in the pre-Mongol period might have caused population pressure in the region which might have been a stimulus for the seasonal use of these marginal areas. Like today, seasonal inhabitants might have originated at least partly from Matcha or Fan.

D. Shelters and caves

In contrast to the neighbouring Aktangi valley rock shelters and caves are a rare feature in the archaeological record of the Argly system (fig. 18).

Figure 18: Shelters and caves

None of these sites yielded substantial traces of non-recent human occupation.

E. Isolated stray finds

Figure 19: Isolated stray finds

Stray finds without any related archaeological features at the spot (fig. 19) are mostly confined to pottery sherds. Most of them seem to be "mediaeval" in date (as far as they could be determined). In sharp contrast to the prospection results from the Aktangi system there are almost no stray finds of iron slags and furnace fragments. The only exception is the site Kabutag-2 where a large quantity of slags and furnace fragments were recorded. But this site is located at the feet of the Argly pass thus in immediate neighbourhood of the Aktangi system to which it, therefore, seems economically related. The most remarkable stray find from the upper Argly valley is a chopping tool (14,6 x 10,3 x 7,1 cm) of one of the eastern hill terraces of the Tukchi valley (site Tuktchi-4).

Figure 20: Chopping tool

Its 6 cm long semi-oval and bifacial cutting edge has an angle of 110ŗ. It is flaked in one of the narrow ends of the regularly oval pebble core (porphyrit). A distinct pebble stone industry with similar chopping tools is known from several Middle Paleolithic (Mousterian) sites in the piedmont region of the Turkestan range (sometimes labelled as "Shakhristan-sai paleolithic"). Another untypical stray find from the upper Argly valley is a grindstone (site Kenkul-17) which is most probably related to one of the nearby mediaeval farmsteads (Kenkul-1 to 6).

2.2 The Lower part of the Argly system

The archaeological record from the lower part of the Argly system (around the present-day kishlaks of Ovchi and Uguk) is constituted by the following groups of material:

- A. An early-mediaeval qal'a

- B. Watchtowers

- C. Burials

- D. Non-recent irrigation structures

- E. Stray finds in different parts of both kishlaks and their immediate surroundings

A. Qal'a-i-Mugh (site Qal'a-i-Mugh-1)

The early-mediaeval fortress of Qal'a-i-Mugh (lit.: "Castle of the Magus") is situated a the north-western margins of the present-day kishlak Ovchi (see map in fig. 26). It was first mentioned and described by A. I. Bilalov in the course of his investigations of the Basmanda-sai irrigation in 1974.[6] The site is situated at the north-eastern end of a plateau which runs about 4 km from south-west to north-east between the mountains in the north and the plain of the Argly in the south and is intersected by several small wadis.

Figure 21: Qal'a-i-Mugh

Whereas the northern and the south-eastern edges of the qal'a are naturally defended by steep slopes (up to 40 m high), the south-western and western flanks are defended by artifical moats. In addition, substantial remains of fortification walls of mud bricks on stone fundaments can be observed in the south-western edge of the fortress. The inner area of the fortress measuring ca. 135 m from east to west and 37-145 m from north to south is relatively flat, except for a nearly quadratic elevation (ca. 16 x 18 m) at the eastern edge of the fortress which seems to represent the remains of a small donjon or a keshk. Surface findings of pottery sherds date from the 6th and the 7-8th centuries (fig. 27/2, 4, 5). This corresponds to the dating suggested by Bilalov. The location of the qal'a is wisely chosen: It not only provides control over the irrigation oasis of the lower Argly valley but also controls the entry into the Obburdon valley and thus, via the Obburdon pass, the most convenient access to Matcha in the upper Zarafshan valley and to other areas further southwards in Northern Bactria/Tokharistan.

B. Watchtowers

Our prospections identified three further sites which belong to the former fortification system of the lower Argly valley (Qal'a-i-Mugh-2, Qal'a-i-Mugh-4 and Argly-7). Both Qal'a-i-Mugh-2 and Qal'a-i-Mugh-4 are situated some 40 m above the plain, on the steep slope of the plateau, about 1 respectively 2,5 km to the south-west of the qal'a (Qal'a-i-Mugh-1) (see map in fig. 26). Today both sites form small clay elevations of about 10 m in diameter and 1-2 m height. Whereas in the case of Qal'a-i-Mugh-2 no ceramic material could be collected from the surface, some early-mediaeval sherds were recorded in the plain at the foot of Qal'a-i-Mugh-4. Possibly, both sites are of early-mediaeval date and constitute a communication line between the qal'a and the edge of the irrigation oasis (where Qal'a-i-Mugh-4 is situated) towards the upper parts of the Argly valley. A third site of this category (Argly-7) is situated on hill-slope at the north-eastern margin of the present-day kishlak. Obviously, this watchtower holds an important strategic position as it is situatated immediately opposite the branch-off into the Obburdon valley. What is still traceable are remains of pakhsa foundations. Ceramic material, however, was absent from the site's surface. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to suggest that the site Argly-7 dates also to the Mediaeval period when such kind of watchtowers were common in Mawarannahr. A last monument which formerly complemented the fortification system of the Argly valley system was reported to us by the local population in the Uguk branch of the lower Argly system. Today it has completely disappeared because of recent building activities. According to our informants it represented a fortified farmstead in the very centre of Uguk, on a steep slope, ca. 20 m above the Uguk-sai. Its former location is still called "Qal'a" by the local population. Possibly, this fortification should be interpreted as a late-mediaeval refuge.

C. Burials

Burials have been reported by locals from different spots in the lower part of the Argly valley. These informations could be complemented by our own field observations at the site Qal'a-i-Mugh-3 which is situated at the north-western foot of the early-mediaeval qal'a towards a wadi called "Tangiston" (fig. 22; cf. map in fig. 26). Here, recent building activities revealed an unknown number of burials. The remains of four of them were still visible in situ.

Figure 22: Remains of Burials at Qal'a-i-Mugh-3

They were cut open by a recent dredger trench in a hill slope thus displaying a profile roughly oriented towards north-west. Judging from our field observations the grave chambers were constructed either as stone cists (1 case) or as burial vaults made of small and medium sized stone boulders (3 cases). At the time of our inspection on-site, human remains were already removed. But at least the remains of the cist suggest single-burials. As far as observable on-site (i.e. without excavation) all four burials were oriented NW-SE. Both construction and orientation have analogies in early Muslim burials from other cemeteries in highland Ustrushana (Aktangi-7, Kalai-Sar), lowland Ustrushana (Kul'-tyube) and the upper Zarafshan valley (Zosun), thus suggesting a date roughly between the 9th and the 12th century. However, burials at this site don't seem to be restricted to this period alone. Locals report of chance finds of at least four more burials in this area. Unfortunately, all remains of their construction had already disappeared by the time of our prospection. But we were shown two completely preserved ceramic vessels (a jar and a small flacon) which, supposedly, stem from these unrecorded burials (figs. 23 and 27/3). Both vessels can be securely dated to the 5th-6th centuries.

Figure 23: Jar from Qal'a-i-Mugh-3 (chance find)

Further finds of human burials were reported from a spot in the south-western margin of the present-day kishlak. Until now this location is called "Qal'a-i-Zindon" or "Qal'a-i-Sugud" (see below). Finally, a number of small rubble stone mounds have been traced around the site of Uguk-3 which might represent burials. According to our informants this place is considered by locals as the "original" cemetery of Uguk.

D. Non-recent irrigation structures

Today the lower parts of the Argly valley around Ovchi and Uguk are predominantly characterized by irrigated agriculture. This certainly holds true also for earlier periods as remains of two karezes at both sides of the Basmanda-sai gorge between the lower Argly valley and the kishlak Basmanda confirm (fig. 23).[7]

Figure 24: Remains of a Karez at the right bank of the Basmanda-sai

Both karezes probably date from the pre-Mongol period as present-day Basmanda is most probably to be intendified with mediaeval Marsmanda which boomed in the 10-12th centuries as a supra-regional market place for iron tools and weapons.[8] Similar underground channels of probably the same date are known from other areas in mediaeval Ustrushana (e.g. south of Shahriston).

E. Isolated stray finds

As usual, the main category of stray finds in the lower sections of the Argly system are ceramic sherds. A rather unusual stray find was shown to us by an informant in the remote Shagan-valley, about 5 km to the south of present-day Uguk, namely several fragments of an iron mail (fig. 25).

Figure 25: Fragments of a mail from Uguk-1

They supposedly stem from the vicinity of some unclear stone settings (site Uguk-1). Without any archaeological context it is difficult to suggest a definite dating for this find as similar mails were in use in Mawarannahr over quite a long period - up into the 19th-early 20th century. However, the comparatively good state of preservation of the fragments might suggest a rather recent dating (late-mediaeval to 19th-20th century?). As for ceramic stray finds, two spots received special attention in the course of our field work.They were pointed out to us by the local population (cf. map in fig. 26).

Figure 26: Archaeological sites around present-day Ovchi

Figure 27: Sample of ceramic finds from different spots around Ovchi.

1 - Qal'a-i-Zindon; 2, 4, 5 - Qal'a-i-Mugh-1; 3 - Qal'a-i-Mugh-3; 5, 6 - Qal'a-i-Asmākat

The first one is sitated 300-500 m to the south of the qal'a (Qal'a-i-Mugh-1) and streches over two terraces above the right bank of the Argly-sai, near its confluence with the Rabut-sai. Until the late 40s when this spot was opened up for cultivation, substantial settlement traces where supposedly situated at the spot. Still today these terraces are called "Qal'a-i-Asmākat" ("Qal'a-i-Asmokat" in modern Tadjik spelling) by the local population. Though architectural remains have by now completely disappeared, prospections revealed a great number of ceramic sherds at the spot, dating roughly to the early-mediaeval and pre-Mongol periods (7/8th-11/12th centuries) (fig. 27/5,6). The second spot which was closer examined in the course of our fieldwork is now situated in the south-western margins of the present-day settlement, which is called "Zindon" (lit.: "Prison"), "Qal'a-i-Zindon" or "Qal'a-i-Sugud" by the locals. Until its destruction in the middle-eighties a small tepa of ca. 30 m diameter and 1-2 m was situated at this spot (first mentioned by Bilalov).[9] Although today this monument is completely bulldozered and overbuilt by a farmstead, a number of ceramic sherds was collected from its vicinity. One of them seems to date to late Antiquity (4-5th centuries) (Fig. 27/1), others are early-mediaeval in date. Stray finds from Qal'a-i-Mugh-1 and from the Ovchi plain now allow a more detailed reconstruction of the settlement history in the Ovchi area (cf. map in fig. 26): The earliest ceramic record is associated with the find spot of Qal'a-i-Zindon (4-5th century). Hypothetically this earliest traceable site might be interpreted as an fortified farmstead ("usad'ba" in Russian-language publications) or a very small rural castle. However, there is no certainty about the exact chronological relation to Qal'a-i-Mugh. Both sites might at least partly be simultaneous in date. However, for the most part of the Early Middle Ages (6th-8th/9th century) Qal'a-i-Mugh-1 should be identified as the seat of the local dihqān. At the same time, the qal'a might have served as a refuge for the villagers living in the valley. At any rate, the existence of such heavily fortified sites is typical for the pre-Muslim Middle Ages when political structures were extremely fragmented. Internal contentions between several minor principalities as well as the grip of external enemies (e.g. frequent Turkic and Muslim incursions) posed a constant threat to the oasis populations in most parts of pre-Muslim Mawarannahr. This situation only changed after the successive incorporation of Transoxania in the Caliphat respectively its eastern Iranian successors. Consequently, most of the former fortifications lost their importance and were abandoned at that time. The same seems to hold true for Qal'a-i-Mugh-1 which was abandoned at one point after the 8-9th century (however, it has to be kept in mind that Ustrushana became comparatively lately part of the "Dār al-Islām"). In the following period the settlement centre seems to have moved to a more convenient place at the bottom of the valley, which is attested by stray finds of pottery from the 10-12th century at the site of Qal'a-i-Asmākat (this coincides chronologically with the integration of this area into the more centralized Sāmānid and Kharakhanid states which provided more political and economic stability than the earlier minor principalities). At the same time, it seems that the settlement retained its older, pre-Muslim, toponym as the name of the pre-Mongol site, handed down by the local population in the form of Asmākat (Tajik spelling: "Asmokat"), contains the well-known toponym formans "kat" (from Soghdian "ka(n)th").[10] It might, therefore, be suggested that the toponym "Asmākat(h)" represents (although in a possibly distorted form) the early-mediaeval toponym of Qal'a-i-Mugh and its rural hinterland.[11]

3. Some preliminary conclusions (by way of comparing the result of 2005 and 2006)

After two field seasons we can now clearly determine and classify the presence of mobile pastoralists in the sample area by archaeological means. They include barrow grounds, petroglyphs, shelters and caves as well as stone enclosures (herdsmen's stations). Notably the barrow grounds constitute an important new source for the history of pastoral-nomadic groupings in this part of Central Asia which will have to be explored by further field work. At the same time our investigations in 2005 and 2006 revealed considerable differences on a micro-regional level even within one and the same high mountain zone: Whereas the archaeological record in the Aktangi system is dominated by "compact" settlements and scattered herdsmen's stations respectively rock shelters, the Argly system offers a totally different spectrum of types of sites: barrows, petroglyphs, single farmsteads and marginal oasis settlements. Partly, these differences might be explained ecologically as the Aktangi system seems to be more "alpine" in character than the more arid Argly system (at least judging from their present appearance). Other possible explanations might be related to external and basically historical factors. Thus, the Argly system is even more secluded than the Aktangi valley, communicating with the lowlands to the north only via a very narrow and difficult mountain gorge (fig. 28).

Figure 28: Mountain gorge between the Argly valley system and Basmanda

Notably the upper part of the Argly system with its multitude of dead end tributary valleys is extremely peripheral in character. This "remoteness" might at least partly count for the fact that many of these valleys were chosen - most probably by mobile pastoralists - as burial areas. If this assumption turnes out to be true, the upper Argly valley would constitute a major burial area of pastoral groupings in Ustrushana. Similar differences between both valley systems can be observed for the pre-Mongol Middle Ages: The Aktangi system is characterized by a stimulated development of compact settlements notably in the lower sections of the valley system. These settlements seem to have been integrated in the market economy of the urban central place in the nearby Shahriston oasis and beyond - they probably supplied these markets with products of the high mountain zone (iron and products of cattle breeding) and received in return products of urban industries (e.g. glazed pottery). In contrast to that, settlement in the Argly valley was dominated by seasonal single farmsteads in the upper sections of the valley systems whose ceramic record seems distinctively less "urban" in character (almost complete lack of glazed pottery) - an observation which also holds true for the ceramic record from the irrigated lower section of the Argly system. Thus, in neighbouring valley systems different settlement structures seem to evolve on the basis of a different external grip on these highland valleys.

Team 2006 (from left to right) - Abdulhamid Hamidov (driver), Matthias Gütte,

Usman Eshankulov, Alexander Puk, Sören Stark, Nabi Rahimov

Notes

[1] Special thanks go to Matthias Gütte who prepared all maps and plans.

[2] Bilalov, A. I. 1978: "O rabote gornogo arkheologo-topograficheskogo otryada STAKE v 1974 g.", Arkheologicheskie raboty v Tadjikistane 14 (1974), pp. 356-358

[3] Bilalov, A.I. 1980: Iz istorii orosheniya Ustrushany, Dushanbe, p. 46 (=Material'naya kul'tura Ustrushany, vyp. 4)

[4] Voronina, V.L. 1980: "Pamyatkiki Kalinabada i ego okrestnostei", Arkheologicheskie raboty v Tadjikistane 15 (1975), 324-335; Negmatov, N.N. 2003, "Istoriko-kul'turnaya oblast' Ustrushana" (=Material'naya kul'tura Ustrushany, vyp. 5), In: Drevnyaya Ustrushana: Goroda, ikh lokalizaciya i khronologiya, Dushanbe

[5] Fedchenko, A. P. 1873: "Kariz", Materialy dlya statistiki Turkestanskogo kraya, Sankt-Peterburg 1873, p. 91; Idem 1950: Puteshestvie v Turkestan, Moskva, p. 149; Bilalov, A.I. 1973: "K istorii orosheniya Ustrushany (bassein Basmandasaya), Izvestiya AN TadjSSR, Otdel. obshch. nauk 2/72 (1973), pp. 32-33; Idem 1980: Iz istorii orosheniya, pp. 45-47

[6] Bilalov, "O rabote", pp. 356-358

[7] These Karezes were first mentioned by Fedchenko ("Kariz", p. 91) and later investigated by Bilalov ("K istorii orosheniya, pp. 32-33; Iz istorii orosheniya, pp. 45-47).

[8] This identification is contested by L. Sverchkov. However, Sverchkov's recent proposal to identify mediaeval Marsmanda with one of two sites to the south of Bakhmal in the Upper Sanzar valley ("Zamok Myk i ego okruga", in: Drevnii Zaamin, Tashkent 1994, p. 61) is problematic for several reasons: Sverchkov is basing his arguments mainly on al-Idrīsī's geographical work (Kitāb Nuzhat al-mushtāq fi 'khtirāq al-āfāq) which reads: "And between Marsmanda and Nūjkath (there are) two days (of travel); and between Marsmanda and the fortress Mīnk (there is) a long day's journey." (ed. Naples-Rome, p. 506, l. 2-3; translation by E. Wakelnig). At the same time Sverchov wants to locate mediaeval Nūjkath at the present-day kishlak Nushkat in the lower Sanzar valley. However, Sverchkov seems to overlook that a few lines earlier (p. 505, l. 17) the same Idrīsi states: "And close to the aforementioned city Bunjikath there is the city Marsmanda" (translation by E. Wakelnig). The following conclusions might be drawn from this: 1) Idrīsī, probably a native from Ceuta who later lived at the court of the Norman kings in Palermo, never traveled beyond Spain, Sicily and North Africa. With regard to toponyms and distances in Mawarannahr he was obviously dependent on the reports of others and, therefore, easily exposed to errors (not to speak of the errors of later copists). Consequently, the mention of Nūjkath in the passage in question should be used with utmost care as this small and little known town never figures in any other extant itinary. Instead, it seems much more likely that "Nūjkath" (one manuscript has "Nījkath") is but a mere corruption of the far more important capital of Ustrushana, Bunjikath, whose name can be in Arabic transcription ( , and many other variants) easily corrupted into Nūjkath or Nījkath. 2) Idrīsī's statement that Marsmanda is situated "close to" Bunjikath is perfectly true for present-day Basmanda but hardly acceptable for Bakhmal in the Sanzar valley. Even if we assume the location of Bunjikath at the site of Shahriston, the communication between the Sanzar valley and the Shahriston valley is rather difficult: The only convenient route leads via Zaamin whereas any shorter route has to make use of a multitude of difficult mountain pathways over passes up to 3100 m. Contrasting to that, the route from Shahriston to Basmanda via Dalyon-i Bolo is easy and takes about 40-45 km, that is exactly a two days' journey.

[9] Bilalov, A.I.: Iz istorii irrigacii Ustrushany (Material'naya kul'tura Ustrushany, vyp. 4), Dushanbe 1980, p. 46

[10] I would like to thank P.B. Lur'e for his comments on this toponym in a personal communication.

[11] Up to now I was unable to find any undisputable evidence for such an "Asmākat(h)" in a mediaeval source. At first sight, the "Ashkāl al-'ālam", an abridged Persian translation of Istakhrī's "Masālik wal-Mamālik" seems to offer a close parallel by mentioning a town of "Arsmānkath" (Mukhtorov, A.: Amiron va vaziron somonī, Dushanbe 1997, p. 29). However, this is probably a corruption from "Arsbānīkath" or "Arsiyānkath", that is mediaeval Isfana.

by Sören Stark, Seminar for Oriental Archaeology and Art History[1]