Preliminary Archaeological and Geological Investigations

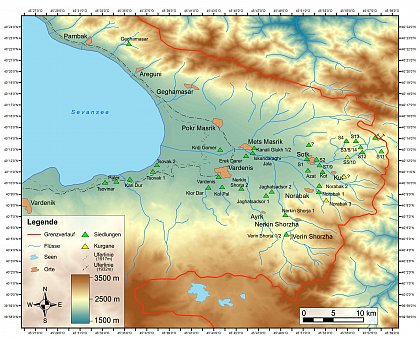

Within the context of a special initiative on behalf of the Saxony-Anhalt Ministry of Culture and in cooperation with the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt, systematic field surveys and initial, detailed archaeological and archaeometallurgical investigations were undertaken from 2010-2015 by the Curt Engelhorn Center for Archaeometry, Mannheim, and the Institute for Petrology and Economic Geology at the Martin Luther University in Halle-Wittenberg. Along with several already known sites, a multitude of other, new sites were able to be surveyed. Information on the settlement network and the general use patterns within the topographically well-delineated bordering natural environment was successfully gathered within the area near the gold deposits. This is the only to successfully reconstruct a possible connection between the settlement network and early gold mining. For this purpose, a total of 41 find sites in the region surrounding the Sotk Mine were surveyed and investigated.

Region Sotk: Dokumentierte Fundorte

aus den Prospektionskampagnen 2010-2013 (Karte:

S. Hüsing, Halle)

This area above all includes fortified settlements atop naturally rounded hills with steep slopes, fortifications on natural cliff faces with Cyclopean masonry, level settlements, find sites with scattered pottery and burial grounds. At the time of the preliminary investigations, only twelve sites were known and superficially examined. Twenty-nine new sites were scouted over the course of the preliminary investigations and initial systematic archaeological surveys were conducted in two selected areas. Hundreds of diagnostic pottery sherds were collected from the new sites during the large-scale surveys and can be attributed to the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age, which also serves as a tentative dating for the sites. The preliminary investigations have made it clear that the entirety of the newly researched (Early) Bronze Age site can be classified as an archaeologically closed settlement system that groups itself in and around the direction of gold deposits and thereby indicates a direct correlation.

Fundort Norabak. Kurgan N1. Skelettlage mit Funden in situ (Foto: R.Kunze, Halle)

As mentioned above, two areas were selected in which initial archaeological work was conducted. The detailed investigation of the site Sotk 2 (settlement) and Norabak 1 (settlement/burial ground) produced numerous conclusions for the initial understanding of the Bronze Age in the area under consideration. In Sotk 2, a natural hill east of the modern-day locality of Sotk, settlement layers encompassing all Bronze Age epochs were uncovered and documented. Particularly impressive in this site was the insight into the Early Bronze Age division of labor, exemplified by obsidian processing. In this context, it is interesting that, in prehistory, obsidian was an extensively traded good, much like gold, and the antiquity of its trade history allows us to sketch out old trade routes and contacts. Research on the spur of Norabak 1 – about 6 km to the south of Sotk 2 – served mostly for the clarification of questions surrounding the dating of the tumulus graves (kurgans) lying in front of the settlement, which can be attributed to the late Middle Bronze Age – the period in which gold was widely used within the Near East.

Detailed results of the surveys have already been published and are quoted in part below:

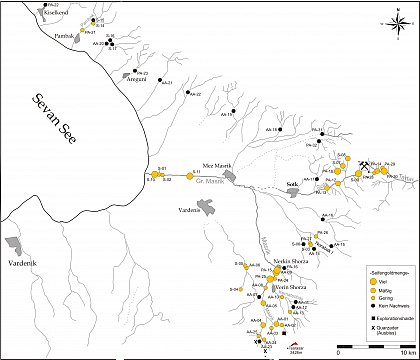

The interdisciplinarity of the project arises from the fact that the prehistoric settlement network along the most important trade routes between the Southern and Eastern Caucasus provides countless indications of a direct connection with gold mining and trade. In order to present this close relationship, the gold-bearing areas along the flowing waters, alluvium, eluvial deposits, and gold veins in mountains were gathered and thoroughly documented over the course of the preliminary investigations. The sampling and analysis of the primary gold ore as well as the geochemical alteration of gold in eluvial, alluvial and fluvial transport thus represent an integral aspect of deposit research. Placer gold was detected in all larger rivers, in sometimes significant amounts, and gold-bearing locations among several streams and rivers was concluded through “negative evidence”.

Beprobungspunkte der

Goldwaschversuche mit

Verteilungsmuster (Karte: D. Wolf,

Halle)

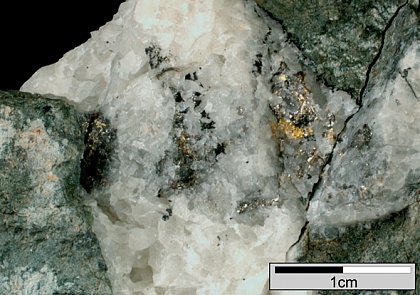

Here, it is important to consider that, in this region, no anthropogenic regulation of gold-bearing rivers and streams has occurred and thus still corresponds to prehistoric times, which is a stroke of luck for the sampling of prehistoric gold sources. The natural sediment traps of placer gold therefore still preserve unimpeded replenishment of gold particles from the primary reef gold deposits. This ensures that gold can also be analyzed that contains exactly the same composition as the gold extracted and processed during the Bronze Age. An additionally important observation alongside the evidence of natural gold through attempts at gold panning was that, in most of the gold-bearing rivers, significant amounts of gold could be collected within a short period of time even with the simplest of tools. This applies especially to the Sotk, Tartar and Masrik rivers. All in all, it is apparent that the construction, structure and method of mineralization strongly facilitated prehistoric extraction of reef gold. This conclusion is supported by the fact that, in many places, gold-bearing veins stretch out directly beneath the surface and therefore permitted prehistoric soap-gold mining alongside placer gold mining. Because gold-bearing quartz-sulfide veins decompose when lying close to the surface and the sulfide prefers to oxidize in this case, we can conclude that, in prehistoric times, easily extractable or even macroscopically visible free gold was found in the outcropping quartz veins, which was relatively easy to identify; that is to say, very early prehistoric gold extraction was possible from this deposit.

Berggold mit Gangart aus

der Lagerstätte Sotk (Foto: D. Wolf, Halle)

In addition, a large number of visible geomorphological negative forms are located in the surrounding hillsides, which must be interpreted as decomposed former sinkholes. Near-surface and sometimes underground mining was facilitated by the fact that parts of the hard gold quartz veins are surrounded by relatively easily weathered sedimentary rock units. Several at least pre-modern tunnel systems to the north of the research area indicate one such underground mine.

Methodik des Goldwaschens: Waschpfanne & -rinne (Foto: R. Kunze, Halle)

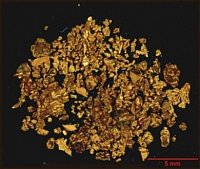

Eluviales Seifengold (0,7g Au aus 50 kg Hangschutt)

(Foto: D. Wolf , Halle)